Somebody else I'm very much looking forward to seeing on 13th May at the Mute Short Circuit event is NON(Boyd Rice) as his music and ideas have been a pretty constant companion over the last two and a half decades or more and he's someone whose activities never cease to be of enormous interest. It's also over fifteen years since the only other time I've seen him live, when he played at Club Disobey at The Hacienda in Manchester on a bill that also featured Pan Sonic (then called Panasonic) and DJ Beekeeper (aka Bruce Gilbert from Wire). I feel that I'm in need of a top-up.

Boyd Rice is also the subject of one of the best things that has come my way for a very, very long time, "Iconoclast", a four hour documentary spread across three discs, in which director Larry Wessel interviews him extensively about his life, career and personal obsessions, as well as many of the people with whom he has associated or collaborated over the years, all this being interspersed with music from across this period, as well as archive footage and images. Here's a trailer for it.

On the first disc, titled "Lemon Grove" after the town in California where he grew up, we find out about his background - how his grandmother was born at midnight on Halloween in a graveyard and how his father, Beverley, chose the most male sounding name possible for his son following the trouble he had had with his own - as well as his childhood wherein he realised early on that things were going to be different compared to other people and that joining the rat race would never be an option. School seems to have been rather a bore for Rice - he says at one point that he only started to learn once he had left - and his childhood and adolescent years were spent dreaming up pranks, visiting tiki bars with his parents and absorbing choice aspects of pop culture such as the music of Bobby Sherman (the lyrical content of which which he likens to Charles Manson's "Cease to Exist"), the fashion designs of Rudi Gernreich and Martin Denny records bought in thrift stores. A strong enthusiasm for occult television series such as "Dark Shadows" and "Strange Paradise" and reading a magazine called "Man, Myth and Magic" all added to the coalescing aesthetic, as well as sending him running to the local library to read everything he could on black magic, the tarot and gnosticism.

In 1969, aged 13, he claims to have truly come alive in a year when, aside from the pilot for "The Partridge Family" being broadcast, Anton LaVey's "Satanic Bible" was first published, Tiny Tim was still popular and in the charts and Charles Manson and his Family committed the Tate/La Bianca murders. He says that to understand anything about Boyd Rice you must first truly understand the importance of the year 1969.

Next came Glam Rock which led to enthusiasms for the likes of The New York Dolls, Gary Glitter and The Sweet, as well as visits to Rodney Bingenheimer's English Disco on Sunset Strip, a place he describes as Fellini-esque in its decadence. More importantly, though, around this time, Rice discovered Dada, this combining powerfully with his playful wish to destabilise the status quo and a growing belief that nothing need ever be viewed from a fixed point or limited to singular interpretations. As well as providing a philosophical foundation for his pranks – in 1976 he was arrested and made the national news for attempting to present America’s first lady Betty Ford with the skinned sheep’s head that he’d been using as a prop at an anti-abortion demonstration that he’d infiltrated – Dada ideas also largely shaped the form of his early artistic experimentation. As well as producing photographs of things that don’t exist and paintings which can be hung in whatever manner suits their owner, he also hooked up with a group of San Francisco Dadaists and began regularly performing sound pieces live, such as having half a dozen music boxes playing simultaneously (a trick he’d learnt off Unity Mitford, I think) or pushing a television set out of a third floor window so that it smashed on the pavement below. Then, at the suggestion of percussionist Z’ev, he self-released his “Black Album” of 1977 which presented an early example of ambient music before such a term existed. Brian Eno, apparently, was nervous when he found out he had some competition. Although it was a very limited pressing and came housed in a plain black sleeve, the record was a success in that copies found their way into the hands of influential people such as journalist Jon Savage, Mute Records’ Daniel Miller, who reissued the album in 1981, and Genesis P-Orridge, as well as Rice’s favourite artist at the time, Arman.

Working under the name NON, initially in collaboration with Robert Turman, the next release was a 7” single, “Knife Ladder”/”Mode of Infection”, which could be played at any speed and using either the conventional hole in the middle or an off-centre second hole to offer maximum playback possibilities. Then came “Pagan Muzak”, a 7” single housed in a 12” sleeve, which took the idea further as, in addition to the aforementioned features, it consisted of seventeen locked grooves, like the closing grooves on a record, which will play continually in a loop until the needle is lifted or pushed on. As Rice says in the film, punk rock music was of no interest to him as it seemed only to offer a harder-edged, faster rehash of what had gone before rather than a radical, ripping apart of all prior conceptions as he was now attempting to do. The first disc ends with NON regularly playing live on the West Coast alternative scene, on bills featuring the likes of The Zeros, Monitor and 45 Grave, Rice playing his roto-guitar which he had built himself. The sound of the electric fan brushing against the strings is described as having been like a bomber taking off in the immediate vicinity.

Disc Two focuses on the decade or so Boyd Rice spent living in San Francisco after relocating in 1978. Working as an alarm agent, he would drive around the city at night dressed in a uniform and carrying a gun and would respond to any security alarms which had been activated, in most cases by rats, he tells us. In addition to this, he made a number of important connections during his time in the city, the first one of these being Ray Dennis Steckler whose 1964 film “The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies”, he says, changed his life. Eager to find out some background on the star of a number of Steckler films, Cash Flagg, whom he admired so much, Rice tells us how delighted he was to find out that director and actor were, in fact, one and the same. Not only this, though, Steckler also turned out to be the director behind a number of the scopitone jukebox music videos, like those for the Kessler Sisters, which he’d recently seen for the first time and which had blown his mind, too.

He also became involved with the team behind the RESearch books and proved to be a lively and inspirational contributor to their “Incredibly Strange Films” and “Incredibly Strange Music” publications, as well as others on “Industrial Culture” and “Pranks”.

One enthusiastic reader of the “Incredibly Strange Films” book was Anton LaVey, founder of The Church of Satan, who contacted RESearch to find out who these people were who shared his taste in films, this leading, in turn, to a meeting with Boyd Rice and the two developing a close and long-lasting friendship. Not only did LaVey share Rice’s interest in obscure cinema and “the dark side” but it appears he, too, was quite a prankster, this all being an integral part of the Satanic archetype we're told, who would adopt different personas such as the U-Boat Captain, the Chinaman and a gangster character for prolonged periods, as well setting off an electronic whoopee cushion device to disorient his visitors. He even programmed his synthesizers to produce a range of classified fart sounds, as well as playing the instruments, along with his collection of organs, more seriously for Rice and friends on weekly all-night visits. Rice went on to encourage LaVey to record some of his music at home and this was released during the mid-1990s.

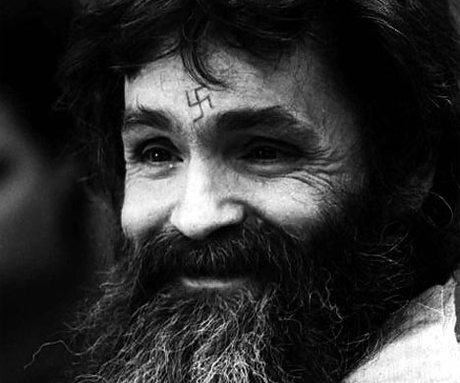

Another person he met during this period and seemingly helped to release music was Charles Manson and Rice gives some details of his eight hour visits to San Quentin which continued upto the day he inadvertently turned up with a bullet still in his trouser pocket from the firearm training he’d recently received for his job, this causing Manson to spend two weeks in solitary confinement and a parting of their ways.

The final section of the disc deals with Rice’s appropriation of the Wolfsangel and Cross of Lorraine as symbols for NON, as well as his interest in Nazi and totalitarian aesthetics which led to his collaboration with Adam Parfrey on the “Apocalypse Culture” publications. This, combined with some jealousies he perceives on the part of the RESearch team, then led to a section of the San Francisco scene branding him a fascist and the city being sprayed with slogans such as “Boyd Rice go home to Europe”. One can't help thinking that posing for a photograph with Amercian Front leader Bob Heick, both holding knives and wearing the group's insignia, didn't really help his cause, although this isn't mentioned in the film. At the disc's close, he has relocated to Denver, Colorado, lured by its anachronistic feel and then being pleased to find “Carnival of Souls” playing at a local cinema on his first night in town.

The final disc then, moreorless, picks up where the last one ended, focussing on the controversy aroused as a result of Rice's growing reputation as a neo-Nazi. In one scene, we see a group of people picketing one of his gigs, objecting rather single-mindedly to lyrics in one of his songs requesting that Benito Mussolini and Emperor Nero "come back", whilst elsewhere one of his friends explains that he is simply somebody engaged in an empirical study of evil, implying that he is prepared to publicly explore areas of taboo that others are squeamish about touching. In one of a series of conversations we see between Rice and Christian talk show host Bob Larson, a man he seems to get along with quite happily, he explains that a totalitarian aesthetic appeals to him because it offers a degree of order which most people lack in their lives and that it calls upon people to apply strategies to achieve their goals, this again being something not undertaken by most people. In amongst this and an excerpt from a radio show where Rice argues rather uncomfortably live on air with the mother of Sharon Tate, Larson asks him, at one point, if he has ever felt like he's in need of an exorcism. Rice explains, "Bob's been working away at me for the last fourteen years or so. He never gives up." Larson is later delighted to hear Rice explain his approach to social interaction, finding that it echoes the sentiments to be found in The Sermon on the Mount.

More stories of visits to Anton LaVey also appear on the disc, as well as details of Rice's involvement with people like Rozz Williams, formerly of Christian Death, his girlfriend Margaret Radnick and The Partridge Family Temple whose member Sean Partridge spends quite a while explaining their background and philosophy. We also see him working on one of his Unpop paintings, hear tales of further pranks, see him and Death in June performing a live version of "People" from the "Music, Martinis and Misanthropy" with improvised lyrics and take a visit to Tiki Boyd's, the bar he designed in Denver.

However, the Boyd Rice I struggle to get along with and which seemed most to come to the fore in the mid-1990s is also present at times on the disc. For example, fired by his experiences at a place called The Lion's Lair in Denver where young girls would, we're told, walk around naked and seemingly sit at his feet, we hear of him sending the younger Gidget Gein a painting of a skull which he'd articulated using the menstrual blood of a thirteen year old girl who we're told he bragged to have deflowered. He also tells us of late night telephone conversations he used to have with Tiny Tim wherein the latter fantasised about Heaven being a place where he could have sex with young girls and of the two of them competing for the attentions of the same girl. He speaks quite admiringly, too, about Tiny Tim's atittude that women are like horses who need steering in the direction their rider wishes rather than being allowed their free will, echoing this with Charles Manson's views that they are like dogs who must be selected and trained from a young age if they are to be truly obedient. Although not mentioned in the film, this is the Boyd Rice who wears a t-shirt with rape boldly printed on it one photograph, who released the single "I'm Just Like You" which skits at the mentally ill under the name of The Tards and who talked of wanting to retreat to a place devoid of "unruly niggers" on his "Hatesville" album of 1995. We do get to see him performing his piece "How God Makes Little Girls" live, though, and much to the delight of a whooping audience but the whole thing comes across as being a bit like something from a school playground and a bit sad. It's one thing wanting to confront taboos and double standards and trying to get up the noses of hypocritical liberals but it's another acting like an arsehole in doing so.

So, by the end of "Iconoclast", Boyd Rice sems to come across as truly representing all that he says he stands for, a manifestation of both the good and evil natures living concurrently in human beings and also someone with a profound love of popular culture from previous decades and an admirable thirst to explore all areas that interest him in great depth, his frustrations that others do not share his loves and enthusiasms in the same way, perhaps, leading to his misanthropic tinges.

This is an amazingly detailed and fascinating set of discs for which Larry Wessel must be congratulated unreservedly and the fact that so much of Boyd Rice still remains left uncovered, such as details of collaborations with people like Rose McDowall on the brilliant Spell album, Frank Tovey on "Easy Listening for the Hard of Hearing" and Coil on the Sickness of Snakes project, his leading role in the 1999 film "Pearls Before Swine", the part he played in releasing records by Johanna Went, Ralph Gean and Little Fyodor, as well as his enthusiasm for sixties girl singers ("The Black Album" apparently features every recorded instance of Lesley Gore singing the word cry and his single "Solitude" sounds suspiciously like it was constructed out of Tammy St. John's "Dark Shadows and Empty Hallways") and people like Abba says more about Rice's achievements and multi-facetedness than oversight on the part of the director. I can't recommend this enough to anyone and it's a snip at $30. Contact him today and buy one.

Whilst you're at it, I strongly recommend trying to find a link to Boyd Rice's appearance on Howie Pyro's Intoxica Radio show from April last year when he went along armed with a selection of his favourite sixties girl records, playing some brilliant stuff like Dusty Springfield's "The Corrupt Ones", Anita Harris' "Upside Down" and one of Peggy March's fantastic German records.